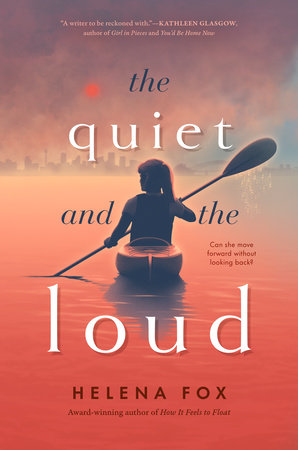

Today we’re revealing the cover for The Quiet and the Loud, a heartbreaking and timely novel about holding too tight to family secrets, healing from trauma, and falling in love, from the award-winning author of How It Feels to Float.

Scroll down to see the cover and read an excerpt!

Summer, nine.

When I was small, almost ten years old, I rowed out with my father to the middle of a lake. It was after midnight—owls prowled, lizards hid, and Mum lay sleeping in the tent beside the water.

We’d arrived at the lake in late afternoon, unpacked the car, and set up camp—a big tent for Mum and Dad, a small one of my very own, for me. Mum banged in pegs with a hammer. Dad fluffed around with the fly and guy ropes, swearing. The lake lap-lapped. I clambered over the shoreline, found flat rocks and skipped them.

At dusk, we three stood at the water’s edge. I held Mum’s hand and we looked out at the lake, the mist, the quiet, fading light. Birds squabbled and settled. The dark dropped in.

Then Mum cooked sausages on the fire while Dad blew up our inflatable dinghy with a foot pump. After dinner, we turned marshmallows on our sticks, watching the skin bubble and blacken. The flames crackled and licked. I crawled into them, listening for stories.

Mum drank her tea. Dad pulled out a beer, hissed the can open. Took a long draw. Mum touched my leg, stirring me. “Time for bed,” she said.

I brushed my teeth with bottled water and spat paste onto the dirt. I kissed Mum and Dad good night, crept into my tent, snugged into my sleeping bag, and went to sleep.

Sometime in the night, Dad woke me with a shake.

“Georgia!” he whispered. “Let’s go have an adventure!”

I could see his glassy eyes, his toothy grin in the dark. I stared at him, confused. I’d been dreaming of apples, of underwater trees? I glanced left, at the canvas wall—just a few steps away was Mum.

“Don’t wake her,” Dad said. “Come on!”

There was something in his voice, something sparking. Say yes, the spark said. Dad’s eyes glittered.

I sat up, shivered out of my bag, and scooted out of the tent. Dad handed me a jacket. We tiptoed like burglars over to where the boat waited. We lifted the dinghy, laid it onto the water, and clambered in.

Then Dad pushed us out into the nothing.

The lake was inky. Gum trees ghosted the shore. The moon ticked across the sky, and the stars blazed.

I looked up. I felt wrapped in it, inside the immensity, the space and silence all around. But I didn’t have the word for that then—immensity—so I said, “It’s really pretty.”

Dad beamed. “Isn’t it just?” he said.

He rowed us until we were nowhere and everywhere. I dipped my hand into the water, scooped and trickled moonlit drops through my fingers. Dad did too. He rested the oars, leaned over the dinghy side, and looked into the lake. He looked into it so long, maybe the sky fell into the lake and the lake fell into the sky, because then Dad looked like he wanted the lake to eat him up.

He said, “Hey, buddy, you can row back, can’t you? Just head for those trees.” And with a plop and a splash, he hopped into the water and swam away.

Oh.

Dad hadn’t surprised me like this in a while. It had been months of a sort-of calm, a sort-of easy, a sort-of happy. I’d seen Mum kissing Dad in the kitchen and smiling into his eyes, and it had been a long time since she’d done that.

But all of Dad was gone now.

I could hear him splish-sploshing through the water. I grabbed the oars and tried to follow the sound. The oars knocked my knees, and I lost one. Then I called and called over the solid lump of lake, but the lake didn’t answer and neither did Dad.

I tried to row back with one oar. I slipped in dizzy circles and all I could hear then was the oar clunking at the lake like a spoon on an empty bowl: scrape, scrape, scrape.

I slumped against the boat side. I would die out here, I knew it. Dad had already drowned. He must have. Lakes could swallow you whole, skies too.

I huddled, knees to chin, and cried with the mucky hopelessness of going in circles and waiting to drown, cried over the water and up. My tears clanged the branches of the sorrowful trees and hissed at the stars.

When I took a breath, I could hear I wasn’t alone.

Mum stood, shouting and screaming, from the shore.